Ames entered the international market 30 years ago, traveling to Uzbekistan to support a mining client in 1994.

Mark Brennan took the initial call asking if Ames would be interested in going to Uzbekistan, where the client was struggling to build a leach pad.

The client explained that they had the needed equipment and were required to use local craft workers, but they would like the help of Ames management. Knowing that sending only management would strain company resources, Mark called Butch Ames to discuss it. Butch said, “Well, they’ve been giving us steady work, and we should help them out.”

Two days after Mark agreed to help with the project, the Minister of Mining from Uzbekistan came to his office, along with two representatives from the mine and two interpreters. Within two hours, the agreement was made to assist with the venture that involved building a 6-million-square-foot leach pad at the Muruntau mine.

Within a week, nearly 40 Ames Construction employees were on their way to the mining town of Zarafshan.

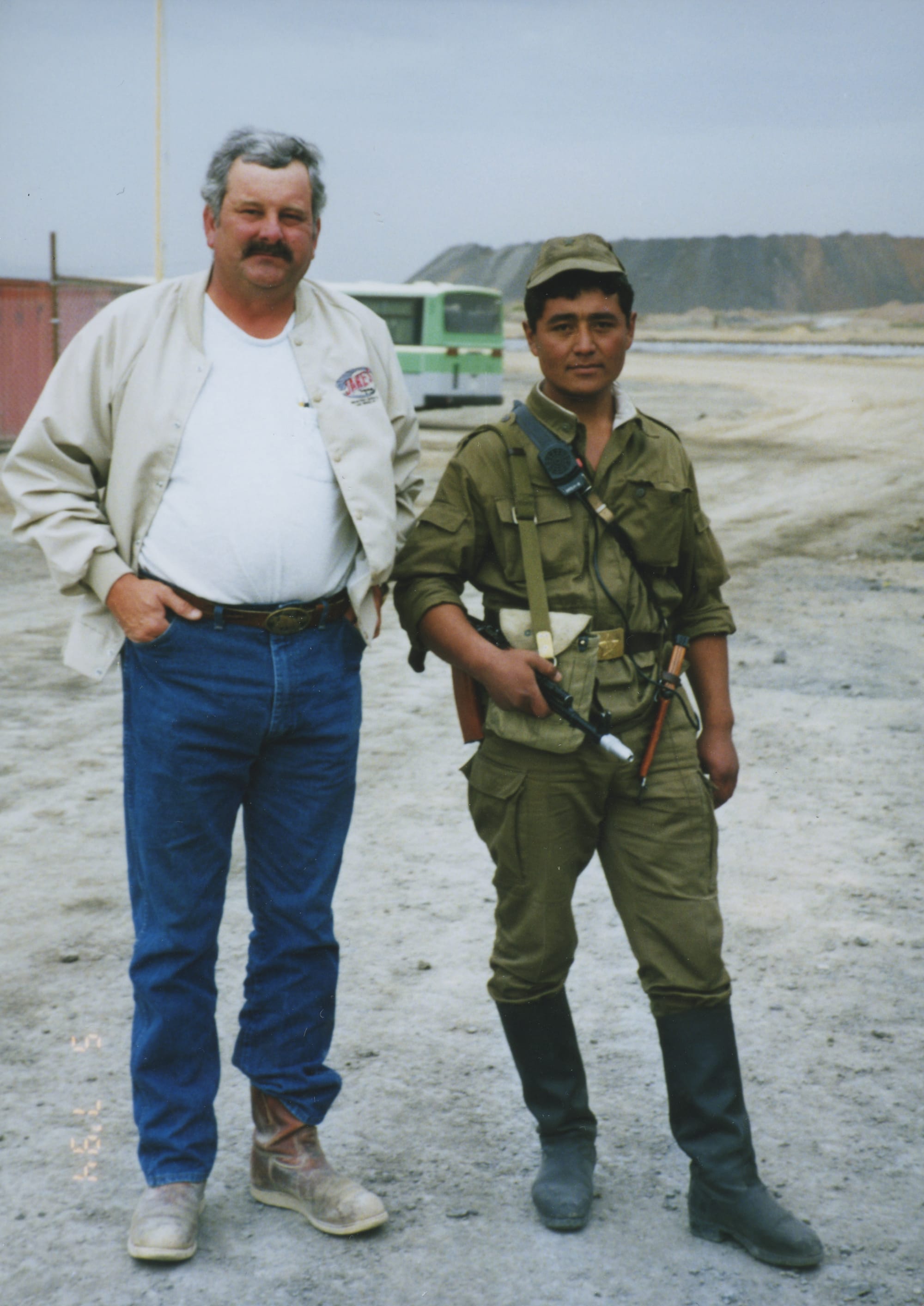

“The man camp was right in the middle of town,” recalled Mark. “At first, the government didn’t want to put up a fence around the camp. We all left the camp for work the first day, and when we returned that night, everything was gone—even the beds. So we put up a fence with security.” Since the mine was only 120 miles from the Afghanistan border, 150 Uzbekistan Army guards were also stationed there.

Once the Ames management team observed the operation, they could see why the client was struggling.

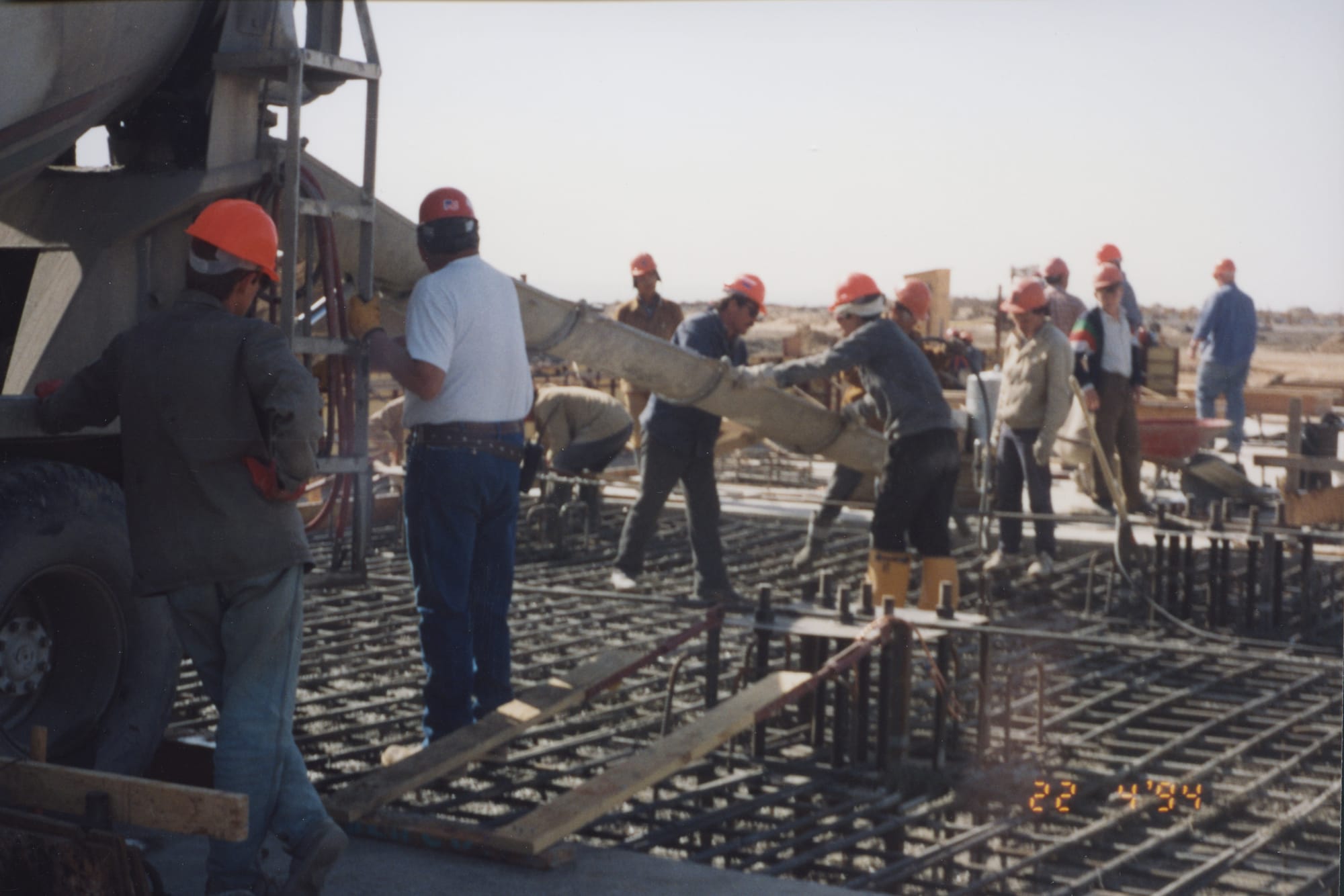

The client had hired an engineering company to do the construction, and in six months, the workers had poured about 120 yards of concrete and moved about 100,000 cubic yards of material. Ames trained the inexperienced workers to effectively construct the new facilities, and in the five months Ames was there, workers poured more than 50,000 yards of structural concrete and performed about 6 million cubic yards of earthwork.

Of the 780 craft people working the job, 30 percent were prisoners.

Mark noted that the prisoners seemed to work harder than the others just for the privilege of being out of prison during the workday. Ames gave commemorative belt buckles to all of the workers, including the inmates.

“The prisoners made frames for them,” said Mark Brennan, “and hung them on the walls of their cells.” Other workers took them home and hung them in their houses like plaques. “That was a big deal to them.” Another big deal was when Ames gave workers an incentive—equivalent to a dollar a day—for each day that they placed more than 120 cubic yards of concrete.